NSO

‘The St. Cecilia Orchestral Society’

The Society was formed by the efforts of Mr. Wm. Bonner, whose desire was to see an orchestra founded for the encouragement of good music in the town of Northampton, feeling sure that the want of such an organisation existed among the musically inclined in the town.’

This is the first entry in the orchestra’s minute-book. Members were invited by an advertisement in the local papers and the first practice was held at the Unitarian Schoolroom on October 24th 1893, when ‘an encouraging commencement was made with 21 Members.’ The orchestra, conducted by William Bonner, met for weekly practices until December 21st, when the members were called upon to elect a committee for the future management of the Society. Isidore de Solla agreed to become the first President, and a committee of eight members was elected, including William Bonner (Conductor) and Charles Furniss (Secretary). The first committee meeting was held after the practice on January 12th 1894 and the following resolution was carried unanimously: ‘That the name of the Society be “The St. Cecilia Orchestral Society”.’ A further meeting took place shortly afterwards at William Bonner’s house, when H. C. Haynes was appointed chairman. After discussion, a number of rules were adopted. These included the name of the Society; that it should be under the control of a committee of 9, retiring annually; that the subscription be 2/6 (two shillings and six pence) a quarter. It was thought advisable that the Society should at present be self supporting. Mr. Bonner’s services as musical director were gratefully accepted.

After resumption of weekly practices early in 1894, the rehearsal venue was changed to the Gymnasium Room in Abington Street—a larger room being needed because of increased membership. The Society’s first concert was given at the Town Hall on Saturday January 20th 1894, in connection with the ‘Saturday Evening Talks’ movement in Northampton. The orchestra consisted of 40 players and the soloists were Miss James (contralto) and Mr. Francis Pickman (baritone). The President opened the proceedings, then the Chairman asked Mr. Bonner to proceed with the programme. After the concert, a vote of thanks was accorded to Mr. Bonner, the orchestra, the vocalists, the accompanist and the President. The programme—comprising a large number of short, ‘light’ pieces, including songs; so different from present-day orchestral concerts—was as follows:

March, Royal George (Bonheur). Overture, La Sirene (Auber). Song, The Holy City (Adams). Graceful Dance from Henry VIII (Sullivan). Song, The Lost Chord (Sullivan). Pizzicato Serenade, Baby’s Sweetheart (Corri). Song, The Devout Lover (Maud V. White). Overture, Bohemian Girl (Balfe). Song, On the Banks of Allan Water. Mazurka, La Czarine (Gaune). Gavotte, Chicago Exhibition (Heins).

Reports in the local press were enthusiastic: ‘The hall was crowded in every part and the audience would have numbered hundreds more if the walls had been elastic ... the performance of the new orchestral society and the reception they met with showed pretty clearly the existence of a considerable body of earnest instrumentalists and of a ready spirit of appreciation on the part of the public. The Society has only been in existence three months, and the progress made is already surprising.’ The orchestra’s AGMs were somewhat festive occasions in those early days. Reports of them indicate a rather light-hearted atmosphere and a rapid dispatch of business (with little contention). The first Annual Meeting and Dinner took place at the Stags Head hotel on June 26th 1894. After ‘an excellent repast’ the Secretary reported on the Society’s first season: excellent results had been attained and, financially, there was a satisfactory balance of £1 13s 8d in hand. ’William Bonner was re-elected as Hon Conductor and expressed his willingness to do all in his power for the welfare of the Society. The remaining committee members were re-elected en bloc, Charles Furniss continuing as Secretary. The Chairman proposed the health of the President who, in his reply, forecast a successful future for the Society. He commented on the enthusiasm of the players—some even carrying large instruments eight miles to the practices! The rest of the evening ‘was very harmoniously spent, songs and instrumental selections being skilfully rendered by the members, Mr. E. J. Tebbutt ably presiding at the piano’. The proceedings were reported at length by the local papers.

The second concert, in the following November, was given to ‘a crowded audience’ and judged to be ‘a grand success’. Noteworthy features were the inclusion of a Haydn symphony and the recitation of monologues by an ‘Elocutionist’, H. C. Haynes—presumably the Chairman! The £10 gain from the concert was used to buy 31 music stands and a cupboard to keep them in. A pattern of two concerts a year was established; one in the spring and the other in the autumn. The Town Hall became the regular venue, although the orchestra occasionally performed elsewhere: for example at the Corn Exchange (later to become a cinema) in the Market Square. Membership of the orchestra increased and 70 players took part in the November 1895 concert. The programme content, in terms of the type of items performed, remained much the same for many years: usually a symphony or concerto, offset by lighter pieces—overtures, suites, incidental music, vocal and instrumental solos. Singers were ever-popular (especially, one suspects, if they had foreign names—real or assumed!) and were usually accompanied by the piano, rather than by the orchestra. For more than 30 years, Ernest Tebbutt was the redoubtable accompanist. The Lost Chord was not only sung but also heard as a cornet solo; other favourites in those early years were The Holy City and Come into the Garden, Maud. The November 1896 concert was notable for the ambitious choice of Beethoven’s fifth symphony; the performance had good press reviews, the players being praised for ‘coming through the ordeal with great credit, playing with a precision and spirit that augurs well for the future’. (In those days, there was no shortage of space in newspapers; on this occasion, a long review gave full details of the programme—including the programme note of the symphony!) Another feature of the event was the debut of Miss Daisy Bonner (14 year-old daughter of the conductor) who played two movements of Mendelssohn’s First Piano Concerto.

Membership of the orchestra remained fairly constant during the remainder of the ’nineties. There was a fair proportion of ladies (about one fifth) but, as yet, none in the wind section. A rather charming custom was to list their names at the head of each string section (the gentlemen trailing behind!) in the programmes. In 1897, a concert opened with the National Anthem to commemorate Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee; and Haydn’s Farewell Symphony ‘caused much amusement’ as the players departed, one by one. In the following year, a Mozart symphony (No. 29) was programmed for the first time, and Lilian Bonner (William’s younger daughter) made her debut with a De Bériot violin concerto. The Bonner family, obviously musically gifted, had a high profile in Northampton’s musical life. William Bonner, by all accounts, devoted himself to the orchestral society and was much praised for his musicianship, energy and enthusiasm. The two daughters performed at a number of concerts.

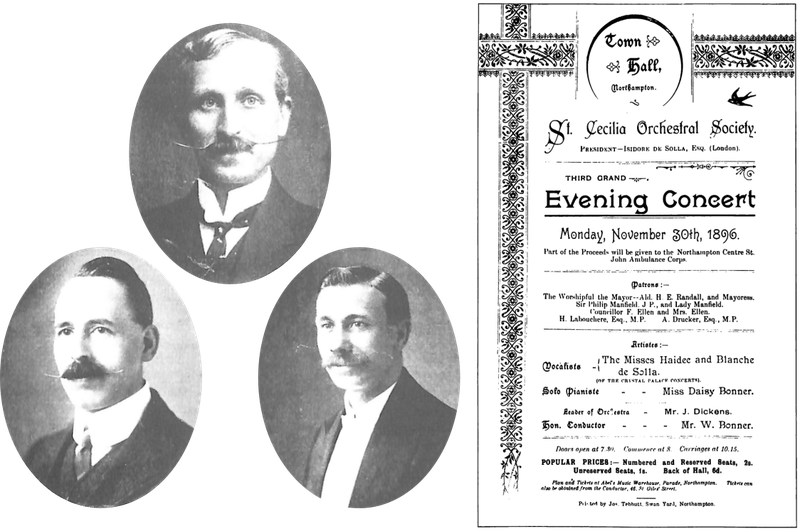

Left: William Bonner, Charles Furniss and Ernest Tebbutt; Right: The first page of the 1896 programme

A new name

In 1932, the orchestra changed its name to the Northampton Symphony Orchestra. There was some hesitation about the change of name; Charles Furniss wondered whether the orchestra could live up to its new title. Perhaps he felt that his fears were justified when a press review referred to dull playing). Two more long-serving members joined the NSO during this decade: Dan Cleaver (cello) and Ron Gibson (violin/viola). In 1937, the name Malcolm Arnold appeared in the programme—the well-known Northampton-born composer had played in the trumpet section, as a lad. The March 1933 concert was distinguished by the first half of the programme (Beethoven Leonore Overture No. 3, Handel’s aria Ombra mai fu and Tchaikovsky’s Pathétique Symphony) being broadcast on the BBC’s Midland Regional Station. A subsequent letter in the ‘Northampton Independent’ complained of the lack of a municipal orchestra in the town—which would be broadcast by the BBC from time to time. The reply from the NSO’s Hon. Secretary doubted the feasibility of maintaining a (presumably professional) orchestra in Northampton, but pointed out that the NSO had given a broadcast and would probably do so again!

Programmes tended to be somewhat conservative throughout the period between the two world wars. Certain favourites were performed regularly: Beethoven symphonies, The Dvorak New World, Tchaikovsky Pathétique, Schubert Unfinished and César Franck symphonies; Grieg’s Peer Gynt Suite, Tchaikovsky and Beethoven piano concertos. The Mendelssohn and Bruch violin concertos and also excerpts from Wagner operas were programmed: Mastersingers, Lohengrin, Tannhäuser, Tristan and Isolde, Götterdämmerung. In 1934, Elgar’s Serenade for Strings was played as a tribute following his death. Twentieth century works were, as yet, rarely performed by the NSO, but two exceptions were Holst’s Oriental Suite and Vaughan Williams’ Songs of Travel (both in 1928). Two of Britain’s leading singers of the day—Elsie Suddaby and Robert Easton—added lustre to mid-thirties concerts. Beethoven’s Seventh was the last work to be played by the orchestra before the outbreak of World War II in 1939; once again, wartime deprivations compelled the orchestra to close down. However, little more than a year after the end of the war, activities resumed (in October 1946) with a performance which included Schubert’s Unfinished and Fauré’s Pelléas and Mélisande suite. For the first time, the name Norah Panting appeared on the programme as principal viola; she was to make a notable contribution to the orchestra in the future. The NSO struggled to keep going in those years and there was a dearth of players—particularly in the string sections. Some talented local musicians were engaged as soloists: Tina Faulkner (a violinist who, led the orchestra on a few occasions) played Beethoven’s Romance in F; Helen Cleaver, Rachmaninov’s Second Piano Concerto and her sister, Sylvia—who had a distinguished career as a violinist—the Beethoven Violin Concerto (these two were daughters of Dan Cleaver, already mentioned—another musical family associated with the orchestra). The first performance with the NSO of the Rachmaninov had, in fact, been given some years earlier by the local pianist, Charlotte Noon. In 1948, Leonard Andrews was appointed Deputy Conductor and his son, Richard, who became another long-serving member joined the violins. Yet another violinist began a long period in the orchestra: Jack Smedley, who retired only recently. Mention should be made, at this stage of the various Leaders of the orchestra. The first three (beginning with J. Dickens) each held that position for only a short time. Then came J. Jackson in 1902, who led the orchestra until the Great War. In 1922, H. Payne took over for 12 years, then two ladies, in succession, for the remainder of the ‘thirties. After the Second World War, the Leader was Leslie Heggs—except for a brief period occupied by Tina Faulkner. Heggs was succeeded in 1956 by Leonard Andrews.

St. Cecilia Orchestra – 1926

After the Wars

In 1949 the attendance of parties of schoolchildren at concerts was mentioned for the first time. This excellent practice has continued, intermittently, until the present time. By the 1950s, ‘modern’ music was beginnig to appear in programmes with more regularity. Examples were: Britten’s Matinées Musicales, Walton’s Crown Imperial, Eric Coates’ Rhapsody for Alto Saxophone and Ireland’s A London Overture. French music (which had featured in a number of programmes for many years—perhaps due to T. G. Carter’s influence!) remained quite popular and in 1954 Bizet’s L’Arlésienne suite and Symphony, and Ravel’s Boléro were performed. Some concerts were given in the New Theatre (sadly, long since demolished) and the Royal (Repertory) Theatre, but the majority continued in the Town Hall. Press notices were mainly favourable: a critic noted a better standard of playing—especially from the strings, and one concert—featuring Rachmaninov’s Second Piano Concerto and Mozart’s Clarinet Concerto—was desccribed as ‘Brave’! lncidentally, the soloist in the Mozart was the NSO's first clarinet, Eric Howlett. Richardson-Jones bowed out as conductor in 1951; he had made a valuable contribution to the orchestra during his long period in office. It is remarkable that, over a period of nearly 60 years, the orchestra had only two conductors. Oswald Lawrence took over and remained for seven years. His replacement, Robert Joyce, conducted only two concerts before leaving Northampton to become Director of Music at a cathedral. He, in turn, was succeeded in 1959 by John Bertalot who held the post for some six years before departing to another cathedral. Thus the pattern of long tenure of office was reversed—for the time being. In the early 1960's, two renowned soloists were engaged: Semprini, a very popular pianist at that time, played the Beethoven Emperor Concerto, and the Northampton-born horn player Alan Civil made the first of several appearances with the NSO in one of the Mozart horn concertos. Other local soloists were the pianist Pamela Loveys and a return of the sisters, Helen and Sylvia Cleaver. Malcolm Arnold’s Second Symphony heralded an era of more adventurous programming.

1964 brought to the orchestra yet another conductor: Graham Mayo, who was to take charge for the next 21 years. Enterprising programming was already evident in his first concert, which included Arnold’s Little Suite for Orchestra. During the next few years, this composer’s works appeared again: a repeat of the Second Symphony, the Oboe Concerto with Leon Goossens, no less, as soloist, and the Cornish Dances. The policy of performing works by Northampton-born composers was continued with William Alwyn’s Fourth and Fifth symphonies, Edmund Rubbra’s Fifth Symphony and Trevor Hold’s A Keele Overture. Other 20th century pieces introduced were: Bartok’s Rumanian Folk Dances, Stravinsky's Suite No. 1, Shostakovich’s Violin Concerto, Britten’s Four Sea Interludes, Elizabeth Maconchy’s An Essex Overture, and, in an American Evening, items by Copland, Barber and Gershwin. Anton Webern’s Konzert Op.24 was performed (with difficulty!) and provoked some controversy. Bruckner entered the NSO’s repertoire in 1970 with his Symphony No. ‘0’; the Fourth and Seventh symphonies were to appear in subsequent programmes. English music was again represented by Vaughan Williams (Symphony No. 5) and Butterworth (A Shropshire Lad). The ‘standard’ repertoire still formed the core of the programmes: Beethoven, Tchaikovsky, Dvorak, Schubert, Grieg and Rachmaninov remaining firm favourites—no surprises here! Notable soloists appearing in the 1960's and 70's were: Denis Matthews (Beethoven's Second Piano Concerto), Amarylis Fleming (Elgar’s Cello Concerto) and the return of Alan Civil (Richard Strauss’s First Horn Concerto) and David Owen Norris—another ‘local’ musician (Grieg’s Piano Concerto). In 1970, Leonard Andrews relinquished the position of Leader, although remaining in the orchestra for a time. Norah Jones, née Panting (Deputy Leader), took his place. A significant development at that time was an increase in the number of concerts given per season: to three, four and occasionally five. As a result, the orchestra was busier: more rehearsals, with fewer for each concert, and more work for the administration. A number of performances were given ‘out of town’, and in Northampton other than at the Town Hall (or Guildhall, as it was by then known). The venues included churches in Wellingborough, Kettering and Northampton (the R.C. Cathedral, St. Matthew's and All Saints), Wellingborough School, Spinney Hill Hall, Northampton High School for Girls—and even the Drill Hall!—where there was a concert performance of Verdi’s Aida in conjunction with the Northampton Musical Society. Another trend at that time was an increase in the number of players and the engagement of more professionals to ‘stiffen’ the orchestra and fill vacancies (although this trend was reversed for a couple of seasons or so because of depleted funds). The role of the orchestra’s committee evolved over the years. Its work became more complex, meetings longer and more frequent. It is interesting to note that, whereas in the past the Secretary was the ‘key’ person in the committee, in latter years the Chairman adopted this role—as Chief Executive, in modern parlance. As President, T. Faulkner Gammage succeeded Lord Hesketh, being followed in turn by Dan Cleaver (briefly, before his untimely death), Dr. Eric Ogilvie, Hilda Benham and John Wilson. The successive Chairmen were Bertram Faulkner, Gammage (later, President), John Bennett and John Wilson.

1983 was a significant year for the NSO. Although the Guildhall, and many other venues, were not lacking in character and charm, they were unsuitable for orchestral concerts—in particular because of their poor acoustics. Northampton is fortunate in having the Derngate Centre, which opened in that year: its excellent acoustic and amenities make it a near-ideal concert hall. The NSO was fortunate at the time in being able to give most of its concerts at Derngate. Graham Mayo did much to build up the orchestra; his painstaking work at rehearsals undoubtedly raised the standard of playing during his regime, which lasted until 1985. Clive Fairbairn was chosen, from a large number of applicants, to succeed Mayo. Fairbairn’s style was more flamboyant than that of his predecessor; his approach to the job tended to be ‘hands-on’—a close involvement with most aspects of running the orchestra. He was responsible for a number of innovations during a relatively short time in office: hosting a Conductors’ Masterclass, participating with the orchestra in performances by the Northampton-based Central Festival Opera, the NSO’s London debut (at St. Giles Church, Cripplegate) and its first recording—Schubert's Rosamunde music, Trevor Hold’s Clare's Ghost, Alwyn’s Scottish Dances and Fauré’s Pavane. Another piece by Hold, Chaconne (commissioned by the NSO to celebrate its first Derngate concert), was programmed in the 1980's; also such contemporary works as Toccata Mechanica by Colin Matthews, Tim Souster’s Paws 3D, Arnold's Tam o’Shanter Overture and Britten’s Serenade. On the lighter side, Viennese Evenings (mainly featuring the Strauss family), usually including a banquet during the extended interval, proved popular. Mahler’s Resurrection Symphony (with Northampton Bach Choir) was a highlight of this decade’s concerts; the Fourth Symphony and Wunderborn songs were also well received—the soloist in the latter being another product of Northamptonshire, David Wilson Johnson, the eminent baritone. Another innovation was that of thematic programming—a season’s concerts being based on a ‘theme’ such as French or English music. or, as in 1989/90, a composer, Tchaikovsky (including Violin and First Piano concertos, Pathétique Symphony, Romeo and Juliet Overture and Serenade for Strings). There was a record attendance (some 1400—almost a full house) at the November 1987 concert: Holst’s The Planets was probably the main attraction, but the other works—Liszt's First Piano Concerto, Vaughan Williams’ Greensleeves Fantasia and Walton’s Crown Imperial—doubtless contributed. Two local cellists should be mentioned, both soloists with the orchestra on various occasions: Robert Bailey (an established professional) and Amy Claricoates (young, up and coming). Yet another outstanding NSO soloist from this area is the clarinettist, Mark Van de Wiel.

The Guildhall, Northampton

The NSO at 100

And so to the present time [1993]. Changes of personnel have brought us our Conductor, Christopher Fifield, and Leader, Trevor Dyson. We were lucky to find a replacement for Clive Fairbairn when he left at short notice to take up another appointment abroad. Christopher Fifield happened to be available at that time and became the NSO’s Conductor in October 1990. Under this gifted musician’s very able leadership, the orchestra has continued to improve. Its expanding repertoire has included collaboration with Central Festival Opera in productions of The Magic Flute, La Traviata, Macbeth and Die Fledermaus. Trevor Dyson was appointed Leader back in 1984, succeeding Norah Jones, who still plays in the violins. We were very sorry to lose our last President, Hilda Benham, who died in 1989. She had devoted herself to the orchestra, and contributed generously to its funds. John Wilson was appointed as her successor, and interprets the role energetically. He is a long-serving violinist in the NSO (since 1964, although a member briefly in the 1930's) and soon joined the committee: first as Orchestral Secretary and subsequently as Chairman, which office he held from 1973 to 1986. He has also been Treasurer for many years. John Wilson has thus served the orchestra very actively over a long period of time and, in particular, has succeeded in obtaining sponsors for many of our concerts. Needless to say, sponsorship, and grants from the Arts Council and Local Authorities, are a vital source of revenue; the NSO is most grateful for this funding. John Wilson's successors as Chairman were, in turn, Arnold Bennett, Jane Moseley and now, Ian Isaac. Others who have given long service include Harold Colman: a versatile musician, well-known locally, who has played violin in the orchestra since 1960, and been Deputy Conductor in recent years. Also Ian McLauchlan, who continues as a violinist after more than 30 years membership and has been a committee member—including a period as Vice-Chairman. The Holemans family—father, mother and daughter—have between them spanned many years as violinists/violists; Anne Holemans being also active in the ‘Friends of the Orchestra’. This voluntary organisation has helped, by fund-raising and in other ways, to foster the orchestra’s needs.Unfortunately, it is in abeyance at the present time but one hopes that, before long, it will be able to resume its welcome activites.

In addition to works by 20th century composers already mentioned, the NSO has also performed Bartok’s Concerto for Orchestra, Stravinsky's Petrushka and Firebird suites, Shostakovich’s Fifth and Tenth symphonies, Britten’s Violin Concerto, Ives’ Second Symphony, Hely-Hutchinson’s Carol Symphony and Ravel’s Piano Concerto in G. In recent times, programmes have become more adventurous and covered a wide spectrum—earning a Performing Rights Society Enterprise Award in 1990. On the other hand, certain ‘favourites’ have each received several performances during the orchestra's existence. ‘Top of the League’ are the following—with the number of performances in brackets: Dvorak, New World Symphony (13). Schubert, Unfinished Symphony (9). Tchaikovsky, Pathétique Symphony (9). Grieg, Peer Gynt Suite (8). Beethoven, Fifth Symphony (7). Beethoven, Seventh Symphony (6). Beethoven, Third Piano Concerto (6). Rachmaninov, Second Piano Concerto (6). Tchaikovsky, First Piano Concerto (6). Mendelssohn, Violin Concerto (6). César Franck, Symphony (6). Beethoven, Violin Concerto (5). Bruch, First Violin Concerto (5). Grieg, Piano Concerto (5).

Members of the NSO are drawn from al! walks of life: business, professional, students, ‘housewives’—and many others. We are fortunate in having a number of instrumental teachers, who enjoy the contrast of playing in the orchestra after a day’s teaching. Rehearsals, for the past several years, have been held weekly at the Northamptonshire Music School. There is now a high proportion of women in the wind sections, as well as in the strings. A striking trend in recent years has been the increasing number of gifted young people in the NSO; they have contributed much to the improved standard of playing. The Northampton Symphony Orchestra’s reputation is such that it can justly be described as one of the foremost community orchestras in the country.